Diastasis Recti - Part 1

What is it?

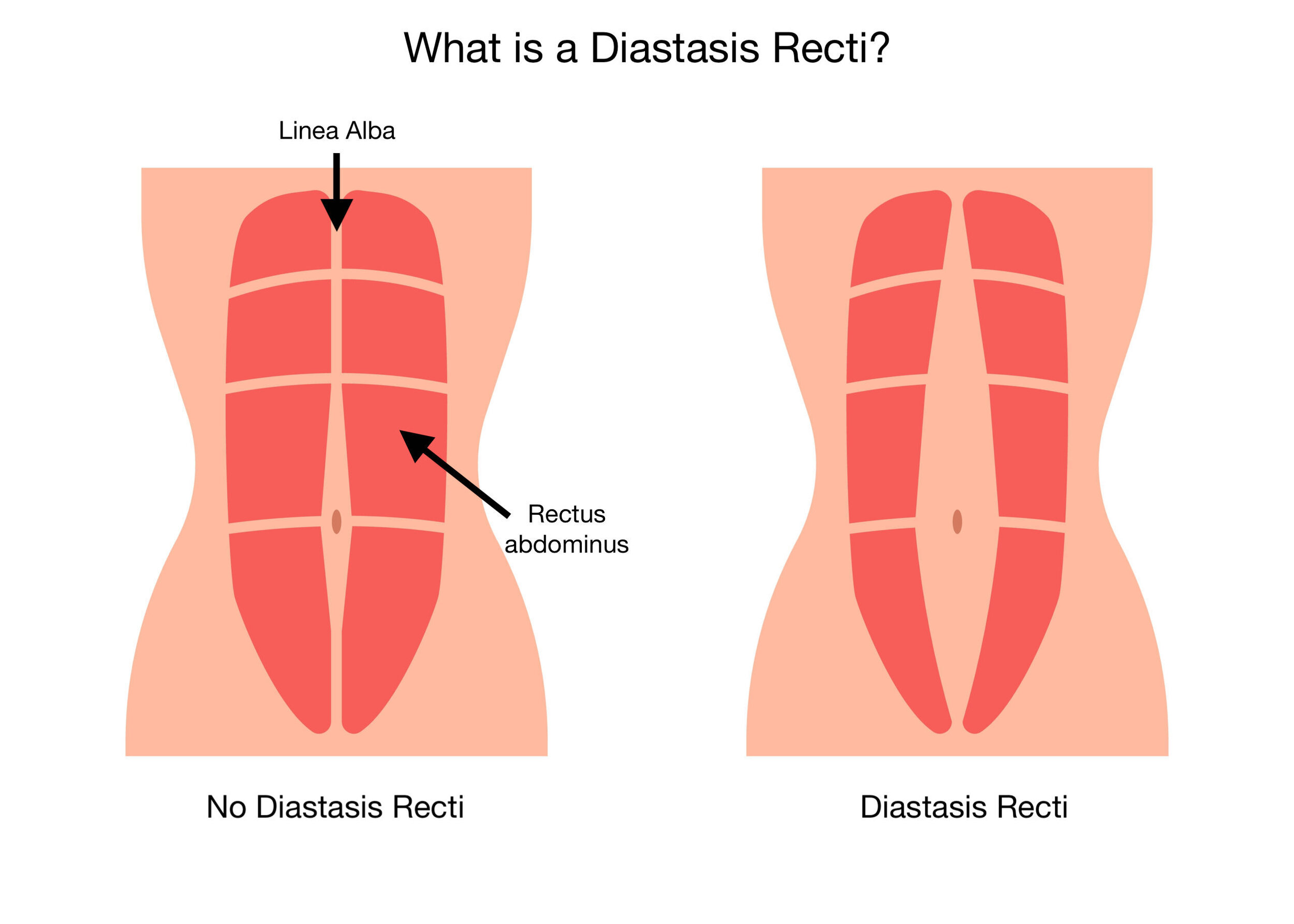

A Diastasis Recti Abdombinus (DRA) or Diastasis Recti (DR) is a midline separation of your rectus abdominal muscles (6 pack abs) along the connective tissue called the line alba of at least 2-3cm.

How to assess for it?

In the video you’ll see me performing a “semi-curl-up test” that is typically done to evaluate the presence and degree of DR - the ‘tenting’ or ‘coning’ of my abdomen along the midline that is visible in the video is a sign of DR, but not a guarantee.

The idea behind this test is that it challenges the functional capacity of the abdominal muscles to control abdominal pressure in this area. One of the functions of these muscles is to control and react to intra-abdominal pressure. What the heck is intra-abdominal pressure? Well, as it relates to function, it’s anything that causes you to “bear down” on your abdomen and usually relates to the reactivity of your diaphragm, core, and pelvic floor. If you have ever poked your abs while you sneeze, cough or laugh and felt them react by tightening up (an example of some activities that cause an increase in abdominal pressure) you’ll feel what I’m talking about. This is why we use a test that challenges function - like the sit-up test - though it has its limitations.

To perform the test, lay on your back and lift your head/shoulders. Then, palpate the linea alba starting at the belly button evaluating the tension along the linea alba and the space between the lateral border of each side of the Rectus Abdominus muscles. Within the industry the accepted standard is a 2-3cm separation of the rectus abdomens at the belly button, above it, or below it, anywhere along the linea alba is considered a Diastasis Rectus Abdominus.

How much is too much?

This is debated, but the industry generally agrees that a 2-3cm gap or more is considered to be DR. The debate comes in around whether or not this is a problem and why.

For starters - there is very poor standardization of taking this measurement throughout the industry. Ultrasound measurement is the most exact, but clinically you’ll hear ‘2 finger’s width or 3 finger’s width’ to equate to the 2-3cm - which is a very inexact science due to the variety in finger size from person to person. From there, it’s not just the width of the gap that is important, but the depth as well. While 2-3cm is the accepted definition it’s not well standardized and there is not a clear understanding for when DR is problematic. (Van de Water 2016, Aswini D 2019)

Also, as you can see in the video, this is a very low threshold test (read - pretty easy). Just because a separation might not be assessed with this curl up, it doesn’t mean a harder challenge wouldn’t elicit gapping or other signs of DR: tenting or coning - more on this idea below. ‘Tenting’ or ‘coning’ is referring to the shape of the abdominal wall as a result of the poor control of intra-abdominal pressure happening at the linea alba. My video shows some of this happening at my mid-line.

Who does it happen to?

Greater than a 2-3cm gap occurs in 100% pregnant of pregnant people by the time the baby is full term. (Fernandes da Mota, 2015)

Something that occurs in 100% of a population is not pathological, it’s normal.

In the pregnant population, the separation that occurs as with DR is a necessary (and normal) adaptation that occurs at the abdominal wall to accommodate growing fetus. Our bodies have such an amazing capacity to create a new life and this is just one of the small things that happen to make this possible! Remember this the next time you see one of those sponsored Instagram ads by a “fit pro” or clinician that is advocating that you can stop or prevent a DR in pregnancy. You can’t! Please don’t click - this is false advertising!

It should also be noted that DR can be found in males or females who have never had children or been pregnant before. And DR is commonly observed in newborn babies, especially premies - it typically resolves naturally in the first few months of infant development. Other risk factors for the non-pregnant population include: frequent fluctuations in weight, or general mismanagement of abdominal pressure - discussed above. Beyond this, risk factors are hard to study and are not widely agreed upon. More research needs to be done to gain a better understanding of these risk factors. (Sperstad 2016, Wu L 2021)

At this point, we know that DR can be present in the non-birthing population. However… very very rarely is anyone evaluated for DR prior to becoming pregnant. I’d suggest that having an understanding of what an individual’s gap is prior to becoming pregnant, would be helpful to reduce fear around DR postpartum. For example, if you knew you started at a 2cm separation, it would be wayyyy less scary to hear that at your 6-week postpartum follow-up that your separation is at 3cm. I’m not necessarily advocating that everyone be evaluated for DR prior to becoming pregnant because I believe that the available data points to the fact that this is a normal occurrence and not at all something to worry about (see more below).

All of this brings a question to the idea of what exactly ‘closing’ a DR separation even means in the first place… More on this in Part 2. Click here to read part 2 of the Diastasis Recti blog!

References

Aswini D, Srihari S K. An Overview of the Studies on Diastasis Recti Abdominis in Postpartum Women. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2019: 14(5): 555900. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2019.14.555900

Benjamin DR, Frawley HC, Shields N, van de Water AT, Taylor NF. Relationship between diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM) and musculoskeletal dysfunctions, pain and quality of life: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2019 Mar 1;105(1):24-34.

Benjamin DR, Van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar 1;100(1):1-8.

Fernandes da Mota, P. G., Pascoal, A. G., Carita, A. I., & Bø, K. (2015). Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Manual therapy, 20(1), 200–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.math.2014.09.002

Gluppe, S., Ellström Engh, M., & Kari, B. (2021). Women with diastasis recti abdominis might have weaker abdominal muscles and more abdominal pain, but no higher prevalence of pelvic floor disorders, low back and pelvic girdle pain than women without diastasis recti abdominis. Physiotherapy, 111, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physio.2021.01.008

Khandale SR, Hande D. Effects of abdominal exercises on reduction of diastasis recti in postnatal women. IJHSR. 2016;6(6):182-91.

Sperstad, J. B., Tennfjord, M. K., Hilde, G., Ellström-Engh, M., & Bø, K. (2016). Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. British journal of sports medicine, 50(17), 1092–1096. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096065

Van de Water AT, Benjamin DR. Measurement methods to assess diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM): a systematic review of their measurement properties and meta-analytic reliability generalisation. Manual therapy. 2016 Feb 1;21:41-53.

Wu, L., Gu, Y., Gu, Y., Wang, Y., Lu, X., Zhu, C., Lu, Z., & Xu, H. (2021). Diastasis recti abdominis in adult women based on abdominal computed tomography imaging: Prevalence, risk factors and its impact on life. Journal of clinical nursing, 30(3-4), 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15568

Hickey, F., Finch, J.G. & Khanna, A. A systematic review on the outcomes of correction of diastasis of the recti. Hernia 15, 607–614 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10029-011-0839-4